Originally this was written as a school assignment about Body Art Among the Natives of America. If I’d followed a chronological order this article should have been published in between my previous two articles (you’ll find them both here: https://cardinalguzman.wordpress.com/tattoo/), but it simply didn’t cross my mind until afterwards…

From my first article in this series you’ll might remember (or you can look it up) that we, through archeological evidence can trace tattooing in Polynesia back to as early as 2000 BCE. You’ll also remember the stories about Captain James Cook and his crew and how they adopted the Tahitian word “ta-tu” or “tatau” when describing this practice. We also had a look at the early American history of tattoo, but I skipped the earlier part about the American history of tattoo – the one about the Indians (today more politically and geographically correct known as Native Americans).

This is the longest article in this series so far and it’s almost like a long list of cultural features among the different tribes and their tattoo techniques. I had to leave out a lot of information about the different tribes and the customs, but if you’re interested you can find more info in the link section.

As many of you already know I’ve asked readers for submissions of tattoo photos and people have sent me their pictures, but for this article I naturally had to find illustrations online (none of my readers are 1800’s native americans…) In the next couple of articles we’ll be looking at the history of tattoo in modern times and then I’ll use readers photos as illustrations.

Chronologically or not, here it is:

The History of Tattoo – Part 3: The Indians

Tattooing has been widely used in North America since before the Christian era, but it was not until the Europeans arrived that it was made written records about the different practices among the different tribes. Tattooing among Native Americans were often performed as religious rituals, or in connection with the wars.

Tattooing is an ancient art form, and back in 1993 one of the most significant Russian archaeological findings of the late twentieth century took place in the Altai Mountains region of Siberia, Russia. The archeologists found a 2500 year-old man who has been called the Horse Man, because he was buried with his horse, and on his right shoulder, he had a tattoo of a deer.

Another, and perhaps more famous find, was a woman from the 5th c. BCE.

«One famous finding is known as the Ice Maiden, excavated by Russian archaeologist, Natalia Polosmak. Three tattooed mummies (c. 300 BC) were extracted from the permafrost of the Ukok Plateau in the second half of the 20th century.» [1]

«The Ice Maiden’s preserved skin has the mark of an animal-style deer tattoo on one of her shoulders, and another on her wrist and thumb. She was buried in a yellow silk tussah blouse, a crimson-and-white striped wool skirt with a tassel belt, thigh-high white felt leggings, with a marten fur, a small mirror made from polished metal and wood with carved deer figures, and a headdress that stood nearly three feet tall. The size of the headdress necessitated a coffin that was eight feet long. The headdress had a wooden substructure with a molded felt covering and eight carved feline figures covered in gold. There were remains of coriander seeds in a stone dish that may have been provided for the Maiden’s medicinal use.» [2]

«Of great interest is the body of the chief from Burial Mound No. 2 at Pazyryk. His body was almost completely covered with tattoos, the main motifs being fabulous animals – for these people were hunters. Horses (from 5 to 22) with lavish harness were also usual features in such tumuli. […] The ancient Altai nomads maintained cultural and trading links with the peoples of Central Asia and the Near East, and thus Chinese mirrors and silk, not to mention woollen textiles from Iraq, have all been found in the burial mounds.» [3]

Often you can hear social ‘scientists’ claim that our modern world is so globalized and that we’re all such a bunch of fucking globetrotters these days, but there’s been connections between the Far East, the West and even the Vikings of the North long before the invention of social so-called ‘science’. The Silk Road, combined with the explorative sea ways of the Vikings, made connections between cultures and in an old viking burial mound at Helgö in Sweden, one of the «most notable finds included a small Buddha statuette from North India and a christening scoop from Egypt».

It’s also well-known that Vikings reached North America approximately five centuries prior to the voyages of Christopher Columbus – an area they called Vinland – Wine Land.

Wikipedia: The name Vinland has been interpreted in two ways: traditionally as Vínland (“wine-land”) and more recently as Vinland (meadow or pasture-land). [4][5]

Which brings me to the subject of the day:

Tattooing/Body art among America’s natives

Tattooing among Native Americans were often performed as religious rituals, or in connection with the wars. Young men had to qualify for such decorations by killing enemies in war, warriors often used their own bodies as “Goal Board” to keep track of how many they had killed. The tattoos were made by dotting the design into the skin with one or more animal bones, or sharp teeth of fish, before they rubbed coal or okra into the wounds.

Tattooing among the Northern tribes

Inuit women often underwent painful tattooing in the belief that they would not find peace in the afterlife without tattoos.

Credit: Atelier Frédéric Back.

The natives of the northern part of the American continent can be divided into 8-10 groups. From Eskimos (or Inuit as they are called) in the north, to Woodland Indians (forest hunters) in the north-eastern parts of the U.S., tattooing was a common way of expression. Most likely tattooing was common in all the areas, but only from the 15th century it is possible to prove this by means of written and illustrated reports from European explorers and plunderers.

At the high plateaus, tattooing wasn’t particularly widespread, but even here there were exceptions.

The Arctic regions of North America were among the last major land areas on Earth as humans settled and it is “only” a little over 4000 years since the first humans walked into this region. Around 20 groups occupy an area on the Arctic coast stretching about 6000 miles, reaching from Siberia to the Eastern Greenland.

Although they have Asian origins, there are many who look at them as a race separated from the Indians, as they are not part of the two other northern breeds; the Algonquins and the Athbascans. Eskimo-Aleut language is spoken in the Arctic, with three subgroups, Aleut, Yupik and Inuit-Inupiaq. Their tools, religion, activities and clothing are very similar.

There are records stating that Eskimos engaged in trade with the Nordic people in Greenland in the 13th century, but the first contact between Eskimos and whites probably took place 500 years or more before Columbus “discovered” the Americas. One group, called the Copper Inuit, managed to avoid contact with Europeans until 1910.

Eskimo women wore tattoos that, along with other facial decorations were considered to increase the feminine beauty. Such tattoos signaled a women’s social status, for example, that they were ready to get married and have children. The tattoos were often very extensive and included vertical lines on the chin with more intricate design by the rear parts of the cheek in front of the ears. The markings were made with needle and thread that was covered with soot and then dragged under the skin following a specific pattern. Piercing was also common, jewelry made of bone, shell, metal and beads were crafted into the lower lip.

The tattooist was an older woman, usually a relative, and according to belief only the souls of brave warriors and women with big, beautiful tattoos were granted access to the afterlife. The men often tattooed short lines in the face, and in the Western Arctic regions, the whale hunting men kept records of their success as hunters with the help of these lines.

Berling Strait Eskimos

The Berling Strait Eskimos lived along the Berling Strait from the Yukon Delta, north to Cape Espenburg and they were both coastal and inland people. Along the coast, they hunted sea mammals and in the inland forests they hunted caribou, grizzly bears, plus small animals and fish.

These people (like most ‘primitive’ people around the world) had a tremendous respect for nature and animals – on what their lives were dependent, and they apologized to the animals because of their necessity to kill them.

This respect was also shown in their masks, amulets and ceremonies. The women had tattooed lines on their faces and some of them also had tattoos on the body. Tattooing begun at puberty, when all the boys and girls were tattooed on the wrists. Boys to mark their first prey, and girls to mark their first menstruation.

Aleuts

Warriors whose ancestors had emigrated to the flatlands of Alaska long before white men had set foot there. When the Russians came in droves in the 10th century in search of fur, this proud nature people were shamefully treated. The men were killed or brought to Russia as slaves, and women were used as prostitutes for “promyshlonniki” (fur traders).

These people had tattoos in the form of intricate ornamentation on the cheeks and under the nose down to the chin.

«The tattoos and piercings of the Aleut people demonstrated not only their accomplishments in life but their religious views. Their body art was thought to please the spirits of the animals and make any evil go away. The body orifices were believed to be highways that evil entities traveled through. By piercing their orifices, the nose, the mouth, and ears, they would stop evil entities, “Khoughkh”, from entering their bodies (Osborn, 52). Body art also enhanced their beauty, social status, and spiritual authority.» [6]

Cree Indians

The Cree Indian stayed at the northernmost part of the prairies, in the border area of the buffalo herds migrations into Canada. This was an Algokin tribe that used the tipi as a home, a leather tent that fits well for nomadic existence. The Cree’s were the largest of the northern Algokin tribes and there were two branches; the lowland Cree’s and Forest Land Cree’s.

Their area reached from south of Hudson Bay, almost to the Great Lakes, east from the Quebec / Labrador peninsula and west to the northern high plateaus. Cree men tattooed themselves, sometimes over the entire body, while their wives were limited to two or three simple lines of the face.

Pacific Coast

In California, the weather was mostly mild, and there was plenty of food. As in all societies throughout history, this means that culture and religion were strongly developed as they didn’t have to spend their time struggling for existence. Where culture is developed you’ll also find body art. Some believe that as many as 300,000 lived in the area at the time the first Europeans appeared. The tribes were different in number, appearance and language, but the cultural patterns were very similar. The three main spoken languages; Athabascan, Shoshoni and Penutian.

With the exception of the Mohave in the south (which I’ll come back to), these were among the least warlike of all the Indians. The first settlers who came across the prairies, saw the snow-capped mountains against the sunrise and called them Shining Mountains, and it was less poetic men who later gave them the more prosaic name of Rocky Mountains.

Yurok

A group called Yurok lived along the coast, near the mouth of the lower Klamath River, and their name means “downstream” at karoke language. It is believed that they are Algonquian in their origin. Tattooing was very common among women. When a girl was 5 years old, she was inflicted a black stripe stretching below the chin on both ends of the mouth. Later a parallel line were applied every 5 years so it was easy to estimate their age. Some women also had more tattoos on their chin to show their tribal affiliation (or perhaps it was to hide their age?!). Yuroke was of the opinion that a woman without tattoos looked like a man when she was older.

«Yurok is a Karuk word meaning “downstream” and refers to the tribe’s location relative to the Karuk people. The Yurok referred to themselves as Olekwo’l, or “persons.”»

«Ceremonial regalia included headdresses with up to 70 redheaded-woodpecker scalps. Every adult had an arm tattoo for checking the length of dentalia strings. Everyday dress included unsoled, single-piece moccasins, leather robes (in winter), and deerskin aprons (women). Men wore few or no clothes in summer. They generally plucked their facial hair except while mourning.» [7]

Tolowa

The Tolowa Indians lived in northwestern California, and the girls were tattooed before puberty with three parallel and vertical stripes on the chin.

«Men wore buckskin breechclouts or nothing at all. Women wore a two-piece buckskin skirt. They also had three vertical stripes tattooed on their chins. Basketry caps protected their heads against burden-basket tumplines. Hide robes were used for warmth. People on long journeys wore buckskin moccasins and leggings. Both sexes wore long hair and ornaments in pierced ears.» [8]

Hupa

Hupa. Mr. McCann measuring dentalium shell money against tattoo marks on his forearm. Photograph by Pliny E. Goddard, Hoopa, Humboldt County, 1901 (15-2947).

Credit: Hearst Museum Berkeley.

Hupa Indians lived along the lower portion of the Trinity River in northwestern California. Hupa women had three broad vertical lines on the chin and sometimes tattooed marks at the ends of the mouth. A special type of shells were used as means of payment among Hupa tribes, and the most common way to measure the “value” of them was to compare five shells of equal size with a series of tattoos on the inside of a man’s left forearm. Late in the 19th Century, reserves were made – one of them was established in Hoopa Valley, so the Hupa had no problems with relocation like many other tribes had. To this day they are one of the largest tribes in California, still with a strong ethnic identity.

«The 85,445-acre Hoopa Valley Reservation (1876; Humboldt County) is the largest and most populous Indian reservation in California.

Men wore buckskin breechclouts or nothing at all. Women wore a two-piece buckskin skirt. They also had three vertical striped tattoos on their chins. Basketry caps protected their heads against burden basket tumplines. Hide robes were used for warmth. People on long journeys wore buckskin moccasins and leggings. Both sexes wore long hair and ornaments in pierced ears.» [9]

Chimariko

«The Chimariko were an indigenous people of California, who primarily lived in a narrow, 20-mile section of canyon on the Trinity River in Trinity County in northwestern California. Originally hunter-gatherers, the Chimariko are possibly the earliest residents of their region.» [10]

We know that Chimariko women began to decorate themselves early in life and that this was done with a stone knife on the chin, cheeks, arms or hands – a technique also used by Shasta Indians (for shasta Indians tattooing was not enough: they flattened their heads for aesthetic reasons). Some Cahto Indians also wore tattoos: perpendicular lines on the forehead, chin, chest, wrists, or legs of both sexes.

Different Tribes – Different Techniques

As the observant reader probably have guessed, there wasn’t a lot of tattoo shops and equipment at the time, but ingenuity was not scarce. For example: if a blue-green color was wanted, coloring from a special type of grass, or cobwebs, was rubbed into the wound. Maidu tattoos were made by puncturing the skin with bones, pine needles or bird bones, and then a red pigment was rubbed into the skin. Men could also be decorated with vertical lines that rose from the root of the nose, an expression which was also applied to the chest, stomach and arms.

Alfred L. Kroeber has pointed out in Handbook of the Indians of California (1919):

«The Maidu are on the fringe of the tattooing tribes. In the northern valley the women wore three to seven vertical lines on the chin, plus a diagonal line from each mouth corner toward the outer end of the eye. The process was one of fine close cuts with an obsidian splinter, as among the Shasta, with wild nutmeg charcoal rubbed in. For men there existed no universal fashion: the commonest mark was a narrow stripe upward from the root of the nose. As elsewhere in California, lines and dots were not uncommon on breast, arms, and hands of men and women; but no standardized pattern seems to have evolved except the female face.» [11]

Konkow Maidu designs were made by cutting the skin with a sharp flint, and then rub the area with coal. Ninsean women got their color from the juice of a blue flower. Miwok tattooed zigzag and vertical lines on the chin and cheeks, and in some cases around the neck. Tubatulabal women used cactus spines to create patterns and coal color. The Pomo is most famous for being capable basket weavers – not their tattoos (which were scarce), and they are also known for their active participation in the American Indian Movement.

Pioneer: Olive Oatman was taken in by the Mojave tribe after her family was killed. The Mojave tattooed her chin to ensure her passage into the afterlife. Credit: Getty Images/Daily Mail UK

Mohave / Yuma

The Yuma People (Quechan, also called Yuma, a native people of Arizona) lived on the riverbeds of Colorado River and they consisted of Yuma and Mohave. Yuma is an O’odham word for “People of the River.”

Their territory consisting of a narrow and very fertile strip of land on either side of the river. Both sexes adorned themselves with tattoos that could be very elaborate. Elaborate face tattoos and face paint was widely practiced among the women, and these tattoos indicated a woman’s status and familial ties. Men also wore nose and/or ear rings. It was their belief that a person without tattoos was not accepted in the next world/the afterlife, but rather gained a foothold in a rat hole after death had occurred. Tattoos were also performed to give fighters an intimidating appearance.

Revelations and dreams were of great importance for Yuma and they acted accordingly. Each tribe or area, had a civilian leader. The position was often hereditary, but the counselor only had advisory powers. The leader (or ‘the general’) in a war and the scalp preserver had certain authorities. and both got their power through dreams. It was important to take the scalps of war, and every month it was danced in honor of them.

Quechans (Yuma and Mohave) considered war essential to the acquisition and maintenance of their spiritual power and they preferred to fight tribes who lived nearby and shared the same views as themselves. It was normal that both parties lined up in order of battle, and before the actual fighting began ceremonial challenges and battle between men of higher rank were performed.

Prisoners were often taken and they were either killed, or kept as slaves. Yuma warriors also had a weapon that they were very proud of and which they handled as experts: a short stick with a pointed handle. One could either bash the skull of a man with the thick end, or impale him with the pointed … [12] [13]

Dancing Secotan Indians in North Carolina. Watercolour painted by John White in 1585. Credit: Wikipedia

South Eastern tribes

South-East Indians belonged to one of the most advanced societies north of Mexico. They were talented and prolific builders, and their crafts were well-developed.

They were skilled farmers and fishermen, as well as hunters. They lived their lives according to a complicated faith that occupied both the natural and supernatural worlds. They were probably our first environmentalists and they were good at preserving food. Their territory was huge, and had its borders in the East to the Atlantic, South to the Gulf of Mexico, West to Southeastern Texas and North to the upper Mississippi and Ohio Valleys. An estimated 1-2 million Indians lived in this area, and the South Eastern people deviated from the European perception of how an Indian should live and look: they didn’t wear feathers, they weren’t familiar with the vaulted huts or the pointy tents called tipi. They were farmers and lived in large communities near their fields. The heart of each community was the town hall and market square. The houses were solidly built of wood, bark, straw and reeds, and in the northern and rocky parts of the area their houses had walls, but in the milder climate of the south walls were omitted (“If it’s hot, you don’t need a wall” – old Indian slogan).

Because of the warm weather people wore little or no clothes. (“When it’s hot, you don’t need clothes…”?? – Could have been an old Indian slogan?). The men wore a loincloth and women wore a skirt around the waist. The women usually wore their hair long, the men shaved their scalp or plucked out their hair in different patterns, but left the so-called scalp bell.

Each adult male was a warrior, and this scalp bell was a challenge to opponents: «try to take my scalp».

The men decorated their bodies with tattoos or scraping. When a boy got his first name, he was scraped so it became a scar. When he was older and considered a budding warrior, he was given a new name and was scraped again. When he finally had distinguished himself by taking an enemy’s scalp, or maybe his head, arm or leg, he got his last name and several tattoos and scars. Tattooing was very common, especially among the Seminole, Creek and Cherokee. Tattoos were usually blue, but other colors were also used. The designs were flowers, stars, animals, crescent moon and other symbols. Both sexes seemed to prefer tattoos in the form of ornaments, but men were more extensively tattooed.

Cherokee men slit their ears and stretched them with the use of copper wires. Creek: both sexes wore buffalo and deer-hide moccasins as well as extensive tattoos. Boys often went naked until puberty. Rank was reflected in clothing and adornment.

The reason we know so much about this period is two 17th century (1600-1699) artists named John White and Jacques Le Moyne de Morgue. White illustrated and wrote about the Indians who lived in the area where Virginia is today. Le Moyne was commissioned to survey Florida and had extensive travels among the tribes there. Among other things White made an illustration of a tattooed governor of North Carolina in 1585.

English: Mother and child of the Secotan Indians in North Carolina. Watercolour painted by John White in 1585. Credit: Wikipedia

Religion had a special place in the lives of the South-eastern people and they lived leisurely, had large fields and often led war against other tribes. War was regarded as the greatest pleasure, and it was conducted with great cruelty. When a tribe found itself in a state of peace, they complained that they had nothing to do. When the British once tried to persuade the Cherokee to make peace with the Catawba, they protested on the grounds that they needed something to do and if they weren’t having a war with the Catwba they would have to go fight some other tribe. The purpose of the war was not to conquer, subjugate or eliminate another tribe. The purpose was simply to live exciting lives and kill as a sport. Besides, war led to several tattoos …

Both in North, South and Central America ethnic groups have disappeared; either through regular extinction during the conquest and colonial period, or their successors have mixed with the general population, leaving many traces.

However, some Indian tribes have, with great success, managed to avoid extinction. A few of them are actually greater now than before the conquest, such as the Mayans in Central America. The Athabaskan speaking Navajo in Arizona (which incidentally did not practice tattooing) has increased the population from around 8000 in 1850 to ca. 97,000 in 1970. Navajo has also established itself politically through its tribal council, but in general the Indians in Latin America represents a larger and more viable part of the population than the Indians of North America (For example in Guatemala where the native-speaking constitute 60% of the population). The last decades there’s been a more purposeful political activity among Native Americans in both the North and the South.

Florida Indians

Tribes of the Creek Confederacy included the Alabama, Mikasuki, Yuchi, Shawnee, Natchez, Koasati, Tuskegee, Apalachicola, Okmulgee, Hitchiti, and Timucua, as well as many others.

«The reader should be informed that all these chiefs and their wives ornament their skin with punctures arranged so as to make certain designs, as the following pictures show. Doing this sometimes makes them sick for seven or eight days. They rub the punctured places with a certain herb, which leaves an indelible color. For the sake of further ornament and magnificence, they let the nails of their fingers and toes grow, scraping them down at the sides with a certain shell, so that they are left very sharp. They are also in the habit of painting the skin around their mouths of a blue color.» [14]

«All the men and women have the ends of their ears pierced, and pass through them small oblong fish-bladders, which when inflated shine like pearls, and which, being dyed red, look like a light-colored carbuncle. It is wonderful that men so savage should be capable of such tasteful inventions.» [15] http://thenewworld.us/florida-indians-gallery/32/

Narrative of Le Moyne, Jacques Le Moyne

That’s the end of this article in my series on The History of Tattoo. Next time we’ll look at more modern times.

Sources

- Oliver LaFarge “North American Indians” Fredhøis Publishing A / St

- Skin & Ink “September 1997” Larry Flynt Productions

- Skin & Ink “November 1997” Larry Flynt Productions

- Skin & Ink “January 1998” Larry Flynt Productions

- Aschehoug and Golden Dahl’s “Great Norwegian encyclopedia” Kunnskapsforlaget

Online Sources (quoted/checked 30.03.2013)

- [1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ukok_Plateau

- [2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siberian_Ice_Maiden

- [3] http://www.hermitagemuseum.org/html_En/03/hm3_2_7.html

- [4] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helg%C3%B6

- [5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vinland

- [6] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aleut_people

- [7] http://what-when-how.com/native-americans/yurok-native-americans-of-california/

On what-when-how.com you can also search for all the the different tribes mentioned in this article like Mohave, Tolowa, Hupa, Cherokee, Seminole, Creek, etc, etc to read more from my digital source material. - [8] http://what-when-how.com/native-americans/tolowa-native-americans-of-california/

- [9] http://what-when-how.com/native-americans/hupa-native-americans-of-california/

- [10] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chimariko

- [11] http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/WWmaidu.htm

- [12] http://what-when-how.com/native-americans/mojave-or-mohave-native-americans-of-the-southwest/

- [13] http://what-when-how.com/native-americans/quechan-native-americans-of-the-southwest/

- [14] http://thenewworld.us/florida-indians-gallery/33/ Narrative of Le Moyne, Jacques Le Moyne

- [15] http://thenewworld.us/florida-indians-gallery/32/ Narrative of Le Moyne, Jacques Le Moyne

Photo credits in this article

- Mummy of the Ukok Princess. Photo: Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mummy_of_the_Ukok_Princess.jpg

- A tattooed woman. Inuit women often underwent painful tattooing in the belief that they would not find peace in the afterlife without tattoos. Credit: Atelier Frédéric Back, dry pastel on paper, coloured pencil and gouache on frosted cel. http://www.fredericback.com/illustrateur/edition/media_inuit-les-peuples-du-froid_C_0959.en.shtml

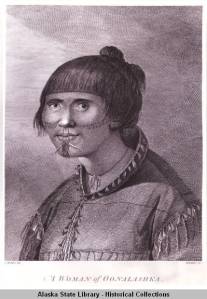

- Aleut Woman. Alaska State Library.

- Hupa. Mr. McCann measuring dentalium shell money against tattoo marks on his forearm. Photograph by Pliny E. Goddard, Hoopa, Humboldt County, 1901 (15-2947). http://hearstmuseum.berkeley.edu/exhibitions/ncc/3_2.html

- Pioneer: Olive Oatman was taken in by the Mojave tribe after her family was killed. The Mojave tattooed her chin to ensure her passage into the afterlife. Credit: Getty Images/Daily Mail UK. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-2270600/History-womens-tattoos-From-Native-Americans-cancer-victims-tatts-instead-breast-reconstruction.html

- Dancing Secotan Indians in North Carolina. Watercolour painted by John White in 1585. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:North_carolina_algonkin-rituale02.jpg

- English: Mother and child of the Secotan Indians in North Carolina. Watercolour painted by John White in 1585. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:North_carolina_algonkin-kleidung03.jpg

More about the history of tattoo:

- https://cardinalguzman.wordpress.com/2011/10/20/the-history-of-tattoo-part-1-polynesia-new-zealand/

- https://cardinalguzman.wordpress.com/2012/08/05/the-history-of-tattoo-part-2-the-americanization-westernisation-of-tattoo/

- https://cardinalguzman.wordpress.com/2013/03/31/the-history-of-tattoo-part-3-the-indians/

- https://cardinalguzman.wordpress.com/2014/01/17/the-history-of-tattoo-part-4-biker-chicano-and-prison/

- https://cardinalguzman.wordpress.com/2016/01/02/the-history-of-tattoo-part-5-japan/

HIstory is wonderful, and the history of the tattoo is equally interesting. I find it a strange idea, but hey that is just me.

This is very interesting,and I ‘ve just come across another study about tattooing and how it meant differently according to different cultures and times….

Thank you for sharing this!

Glad you find it interesting. I’ll post more articles on this subject later.

I think referring to us native as savages is beyond disrespectful!

It’s a bit late to complain about what Jacques Le Moyne wrote in “Narrative of Le Moyne” back in 1564, but: Hey! Let’s not let a good chance to get offended pass us by!

I very much enjoyed reading that. I am glad my chin is still clear- not sure about the afterlife. How many tattoos do you have Cardinal?

My chin is clear and my mind is clear from superstitions about heaven, afterlife, allah and such things. I don’t have a lot of tattoos, but a couple of the ones I have cover quite large areas.

Great article, Cardinal! Yes, how many have you got?

Good question. The answer is: I don’t think that I have that many, but according to my wife I have enough.

Elegant answer and great article, I’m impressed!

Dear Cardinal,

what a great article, very well researched. Thank you for sharing.

Have a great week.

Greetings from the sunny coast of Norfolk

Klausbernd 🙂

Thank you Klaus. I’ve also written and posted two other articles on the History of Tattoo and there’s more to come, but I don’t think I’ll finish the next article very soon.

Excellent essay.

The members of Iroquois Confederacy in my neck of the woods don’t seem to have much connection to tattooing but I still suspect that there’s a history somewhere.

Thanks Allen.

They are very famous for their tattoos. You can see some examples in this post:

http://www.vanishingtattoo.com/tattooed_indian_kings.htm

They tattooed to show off their battle skills by keeping track of how many enemies that they’d killed.

Iroquois women also got tattooed, but for other reasons.

Pingback: Giz Explains: How The Art Of Tattoo Has Coloured World History | Gizmodo Australia

Overall I am fascinated by history, but this is special as it includes such a captivating look into the Native American culture. Well written, thank you!

Thanks for the comment Dalo 2013. I also find this part of history very interesting. The Native American culture is fascinating, but even more so I find the tattoo part interesting (obviously).

You got it…there is so much greatness in cultures and ideas out there to learn. cheers!

Hey I was wondering if I could use this article in a documentary I’m doing about tattoo? It’s about getting rid of their negative stereotypes but I first want to talk about their origins.

Hi Amanda. What’s the format of the documentary? Film?

Will it be available online? Is it for a school project?

Email me if you like: cardinalguzman gmail com

Hi there, just letting you know that the terms “indian” and “eskimo” are no longer used as many people find it offensive. Instead of saying “indian” you would say, first nations, native or indigenous(you may want to do some research to find which groups prefer what, like first nations is preferred in Canada, aboriginal in Australia, etc). You should never use the term “indian,” it is a mistake Columbus made when he thought he had found the Indian Ocean. It is, however not uncommon for first nations elders to use the word, as it is a word they grew up with, so they do tend to use the familiar term. Again, “eskimo” is also offensive, Inuit is preferred now instead(Eskimo was a derogatory term non-inuits pegged to inuits, it means “eaters of raw meat”.)

Hi Lelianna. Thanks for sharing this interesting information.

I’ve picked up from somewhere that the term Indians have been replaced by ‘native Americans’, but I didn’t know it was offensive to be called an Indian. It’s so much shorter and easier to write Indians.

Actually I don’t understand why it’s offensive to use the term. For me the word doesn’t ascribe negative features to the native Americans. If anything, it just shows that Columbus didn’t really knew geography that well. So if anyone should be offended, it’s Columbus (the guy that ‘discovered’ America 500 years after the Vikings had traveled and settled there).

I had no idea that Eskimos was an offensive term either, neither did I know about the etymology of the word. So thanks for sharing that information too! Very interesting!

Anyway, I won’t change the article, since it’s already been published. Now it can stand as a reminder on how our languages constantly change and besides; nothing happens when people are being offended.

But, If I’m to write a similar article in the future, I’ll definitely refrain from using the term Eskimos and write Inuits instead.

Here’s a clip where comedian Steve Hughes talks about people being offended:

The term “indian” isn’t even offensive. As most of them say, they have bigger problems than a geographic mistake. I recommend you a great read: https://www.reddit.com/r/IAmA/comments/5bhzec/iama_american_indian_who_grew_up_and_lived_on_the/

Thanks Alana! I’ll have a look at it later. 😀 If I wrote the article today, I wouldn’t have used the term “indians”.

Pingback: The History of Tattoo quoted in an article | Cardinal Guzman

Good article, thanks.

Thanks Kathey!

Kia ora (hi),

Ka mihi nunui ki a koe mō to mahi tā moko (Thanks so much for your article on tattoo)

It was a great read

Thank you very much for the feedback (and for the translation). 👍

Hi, I was wondering, did the Navajo wear tattoos?

Hi DeAnna. Thanks for the question.

Not according to my sources: The Athabaskan speaking Navajo in Arizona did not practice tattooing.

I’m curious as I’ve seen Navajo/Diné people pictured with tattoos on the chin…

I quite enjoy reading your article reference art before called tattoos. art amongest us Indian folks have reason n 2000:era we still have reason. Today ttaoos are still art t me. now before I pass I want art on my beautiful face. If I have open time capsule, people wl really look n study n admire me lol! Thank you for your hard work so we can understand easier. Peace

Thanks for the feedback Teresa.

I also agree that this was an interesting article with some good research. I do have to let you know however it drove me absolutely insane that you were pluralizing Cree by using Cree’s. There is no apostrophe in a plural!! Also, much of the time the plural of Cree is also Cree just like it is one moose or many moose – but occasionally Crees is also used.

Thanks for the positive and constructive feedback. I’ll keep the plural rule in mind the next time I write something. English is not my native tongue.

Pingback: Premier tatouage américain: les indigènes - Tatouagetattoo

Pingback: Comment l'art du tatouage a coloré l'histoire du monde - Tatouagetattoo

Hey, this is actually a very well written article, I appreciete that.